Ancient fish was hiding in plain sight hundreds of years after its believed extinction, study shows

The modern coelacanth fish is a famous ‘living fossil’, long thought to have died out, but first fished out of deep waters in the Indian Ocean in 1938.

Reconstruction of a large mawsoniid coelacanth from the British Rhaetian (Artist credit: Daniel Phillips).

The modern coelacanth fish is a famous ‘living fossil’, long thought to have died out, but first fished out of deep waters in the Indian Ocean in 1938. Since then, dozens of examples have been found, but their fossil history is patchy. In a new study, published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Jacob Quinn and colleagues from the University of Bristol and University of Uruguay in Montevideo have identified coelacanths in museum collections that had been missed for 150 years.

The fossils identified in the new work date from the very end of the Triassic Period, some 200 million years ago, when the UK lay at more tropical latitudes.

“During his Masters in Palaeobiology at Bristol, Jacob realised that many fossils previously assigned to the small marine reptile Pachystropheus actually came from coelacanth fishes,” says Professor Mike Benton, one of Jacob’s supervisors.

“Many of the Pachystropheus and coelacanth fossils have uncanny similarities, but importantly, Jacob then went off to look at collections around the country, and he found the same mistake had been made many times.”

Jacob, now an Honorary Research Associate in the School of Earth Sciences, said: “It is remarkable that some of these specimens had been sat in museum storage facilities, and even on public display, since the late 1800s, and have seemingly been disregarded or identified as bones of lizards, mammals, and everything in-between, From just four previous reports of coelacanths from the British Triassic, we now have over fifty.”

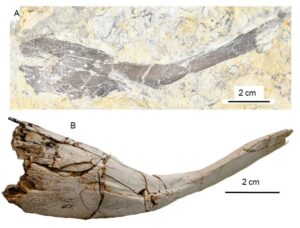

Jacob made X-ray scans of many specimens to confirm the identifications. The specimens mostly belong to an extinct group of coelacanths, the Mawsoniidae, but closely related to the living fish.

Co-author Pablo Toriño, a world expert on coelacanths, located in Uruguay, added “Although the material we identify occurs as isolated specimens, we can see that they come from individuals of varying ages, sizes, and species, some of them up to 1 metre long, and suggesting a complex community at the time.”

Co-supervisor Dr David Whiteside from the University of Bristol added: “The coelacanth fossils all come from the area of Bristol and Mendip Hills, which in the Triassic was an archipelago of small islands in a shallow tropical sea, Like modern day coelacanths, these large fishes were likely opportunistic predators, lurking around the seafloor and eating anything they encountered, probably including these small Pachystropheus marine reptiles, which is ironic given their fossils have been confused with those of coelacanths for decades.”