Forensic Bitemark Analysis for Court Trials is Not Supported by Sufficient Data and “is Leading to Wrongful Convictions”

This additional information is included as part of a press release labeling system introduced by the Academy of Medical Sciences and Science Media Centre. For more details click here.

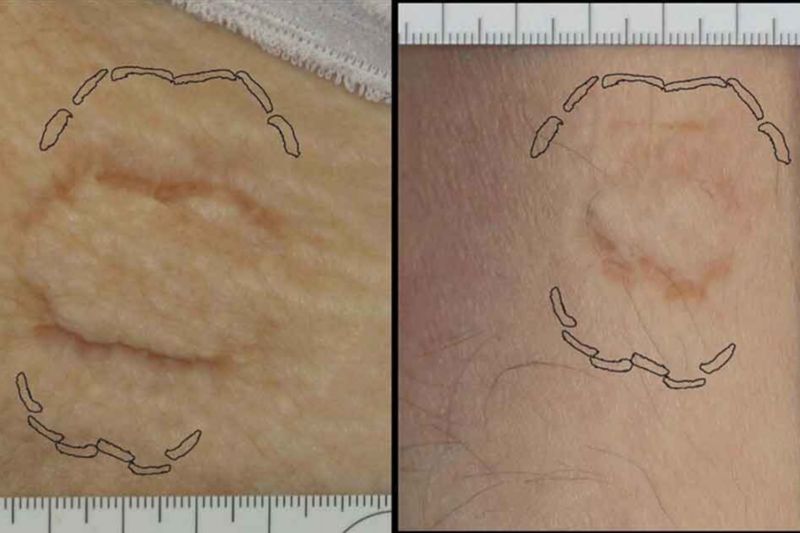

The above bites were created with the same set of teeth. Note distortion among the bites.

Bitemark analysis, evidence often used in trials, is not backed up by scientific research – an analysis of current literature and 12 new studies shows.

Published in the peer-reviewed Journal of the California Dental Association, the research suggests 26 people have been wrongfully convicted, and some even sentenced to death, from the use of this forensic science.

“The scientific community does not uphold the underlying premises that human teeth are unique and their unique features transfer to human skin,” states lead author Mary Bush, Associate Professor at the State University of New York in Buffalo, NY.

“We find bitemark transfer to skin is not reliable and found that within a population of 1,100 people, with just 25% distortion, a significant number of the population could have created the bite.

“Our findings are a cautionary tale of how dangerous the consequences can be when [bitemark analysis] is relied on in trials.”

The team’s dataset noted much more malalignment (and thus fewer matches) in the lower teeth versus the upper teeth. They were also able to examine distortion on actual indentations of the teeth left on skin.

The authors cite the case of Keith Allen Harward who spent 33 years behind bars for a crime he did not commit. The main evidence used to convict Harward was a bitemark on the victim’s skin. A forensic dental expert explained to the jury in such great detail how Harward’s teeth made the bite that his own family doubted his innocence.

“Results from DNA testing proved that Harward could not have committed the crime, and the real perpetrator was identified. Harward was subsequently released from prison,” Professor Bush adds.

Sadly, this is not an isolated case.

The authors note that of the 26 people wrongfully convicted based on bitemark evidence, some were sentenced to death. One of those was Eddie Lee Howard, man sentenced to death in 1994 for murdering a woman. He was convicted on bitemark evidence and spent 26 years on death row before being exonerated. According to the Innocence Project, which works to free people wrongly convicted, “new forensic opinion regarding bite marks and powerful alibi witnesses and DNA from the murder weapon excluded Mr. Howard, proving his innocence.” He was released from Mississippi’s death row in December 2020.

Bush explains that the reliance on bitemark evidence was in part due to the conviction of serial killer Ted Bundy who was convicted mainly on bitemark evidence. “In his 1979 trial, the distinct imprints of his teeth were key evidence and the national attention given to this trial put bitemark evidence on the map,” she says.

The authors’ findings that bitemark evidence is unreliable and should not be used in trials are in agreement with prior studies, including one by the National Academy of Sciences, that there is no scientific data to support the use of bitemark evidence. In 2009, the NAS released a 300-page report on forensic science that found “that the claim that dentists could positively identify a perpetrator by matching their dental patterns to marks on victims’ bodies had never been supported by any scientific study.” Yet, belief in bitemark analysis persists today.

Their findings are also in agreement with a just-published review by the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology that found a lack of support for three key premises of the field: “the human dentition is unique at the individual level; the uniqueness can be accurately transferred to human skin; and identifying characteristics can be accurately captured and interpreted by analysis techniques.” The authors also found a lack of consensus among practitioners on the interpretation of bitemark data and share their thoughts on how to move the field forward.

The authors hope that by presenting their findings at national meetings and publishing in peer-reviewed journals, they can raise awareness of the unreliability of bitemark evidence, potential issues with the evidence and the possible liabilities of testifying at trials.