Testing of primary school pupils promotes culture of division, say experts

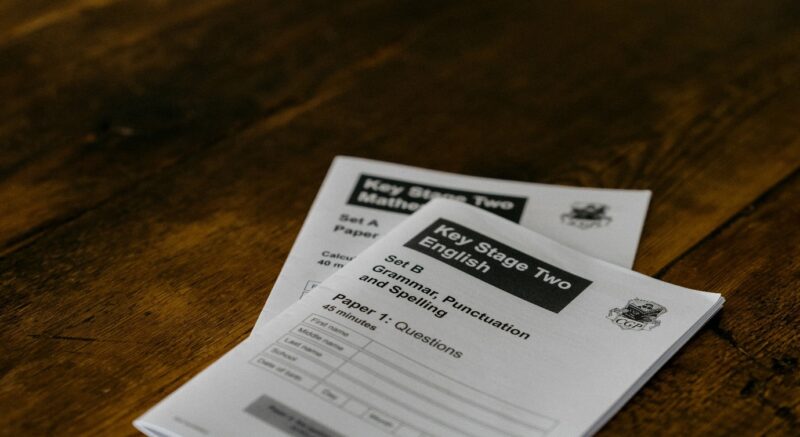

* Statutory Assessment Tests (SATs) (see picture) influence a school’s performance ranking

Study shows children are removed from normal lessons or playtime to plug gaps in their learning and be ‘fixed’ academically, ready for SATS

A fear of poor SATs results is driving headteachers to separate pupils by ability despite the impact on children’s self-esteem and confidence, according to a study by researchers from UCL published in the peer-reviewed British Journal of Sociology of Education.

The findings, based on a survey of nearly 300 principals of primary schools in England, provide new evidence of a high-stakes culture around testing where some pupils are prioritised above others and physically segregated from them.

More than a third (35%) of headteachers said SATs were the reason for grouping children into different ability sets for English, and just under half (47%) for maths, according to the results which also include in-depth interviews with school principals.

Other practices adopted by schools include targeting resources at pupils on the borderline of passing SATs at the expense of ‘hopeless’ cases. The most significant finding was the growth of ‘intervention’ sessions where children are removed from normal lessons or playtime to plug gaps in their learning and be ‘fixed’ academically.

The authors warn that these approaches are part of a ‘potentially damaging’ system where some children are made to feel inferior and which raises questions about how groupings ‘might exacerbate inequalities’.

A debate is needed, they say, about the consequences for primary school children of high-pressured learning assessments, and also for staffing and resources.

“These forms of disciplinary power are encouraged by the disciplinary function of SATs themselves,” says Dr Alice Bradbury from UCL Institute of Education.

“They place pressure on headteachers to prioritise results over the broader purposes of education.

“The SATs are in themselves a practice of division, designating children as at age related expectation (ARE) or not. This binary between success and failure, passing or failing, is a brutal division of children at age 11.

“Early evidence from teachers suggests that there is a strong desire for change following the (Covid) crisis, including the removal of testing.”

Standard Assessment Tests (SATs) are used to assess a child’s educational progress and form the basis of school league tables. The most significant (Key Stage 2) take place in May of the final year of primary education (year 6). For this type of testing, the focus of recent research has been largely international, not on how schools in England are affected or on headteachers’ views.

This study involved an online survey from March to June 2019 of 288 heads about the impact of SATs in general and on issues such as staffing and extracurricular sessions. Comprehensive interviews were also conducted with 20 headteachers at a range of schools across England.

Education leaders at faith schools, academies and community primary schools were among those who took part, with ‘good’ the most common Ofsted rating.

The research focused on the impact on teachers and children from assessment policies which put pressure on schools.

The findings showed evidence of three approaches towards separating children in relation to SATs. The first was dividing by ability into sets, despite what the authors say is ‘increasing evidence of the disadvantages’. In some schools, pupils physically moved from their normal class to different rooms/teachers, and some were even streamed permanently.

Several heads expressed concern about putting children in sets and some rejected the practice. One headteacher commented that ‘pupils get into a psyche of failure because they’ve always been in the bottom set’.

Another approach which was commonplace involved ‘booster’ sessions – singling out children on the cusp of achieving a benchmark SAT grade. These are a feature of educational ‘triage’ where students are sorted into who will fail, pass with help, or succeed without extra support.

The authors also identified a new variant of this triage system which they say has been triggered by the ‘increasing complexity of school league tables’. These involved pupils on the borderline of reaching ‘greater depth’ (above the expected level for year 6) who are given special support, for example, before school and during holidays.

The final practice was what the authors call ‘intervention culture’ where some pupils are withdrawn from normal lessons to resolve ‘gaps’ in their learning. They say this intensifies division by excluding those children in need of additional help from other parts of the curriculum.

The authors acknowledge that divisions created by these practices would not disappear entirely without SATs, which are currently suspended because of the pandemic. However, they suggest these tests might be replaced with ‘more nuanced ways of understanding a child’s attainment’. They add: “There can be no triage or ‘cusp’ if there is no benchmark to judge them by.”