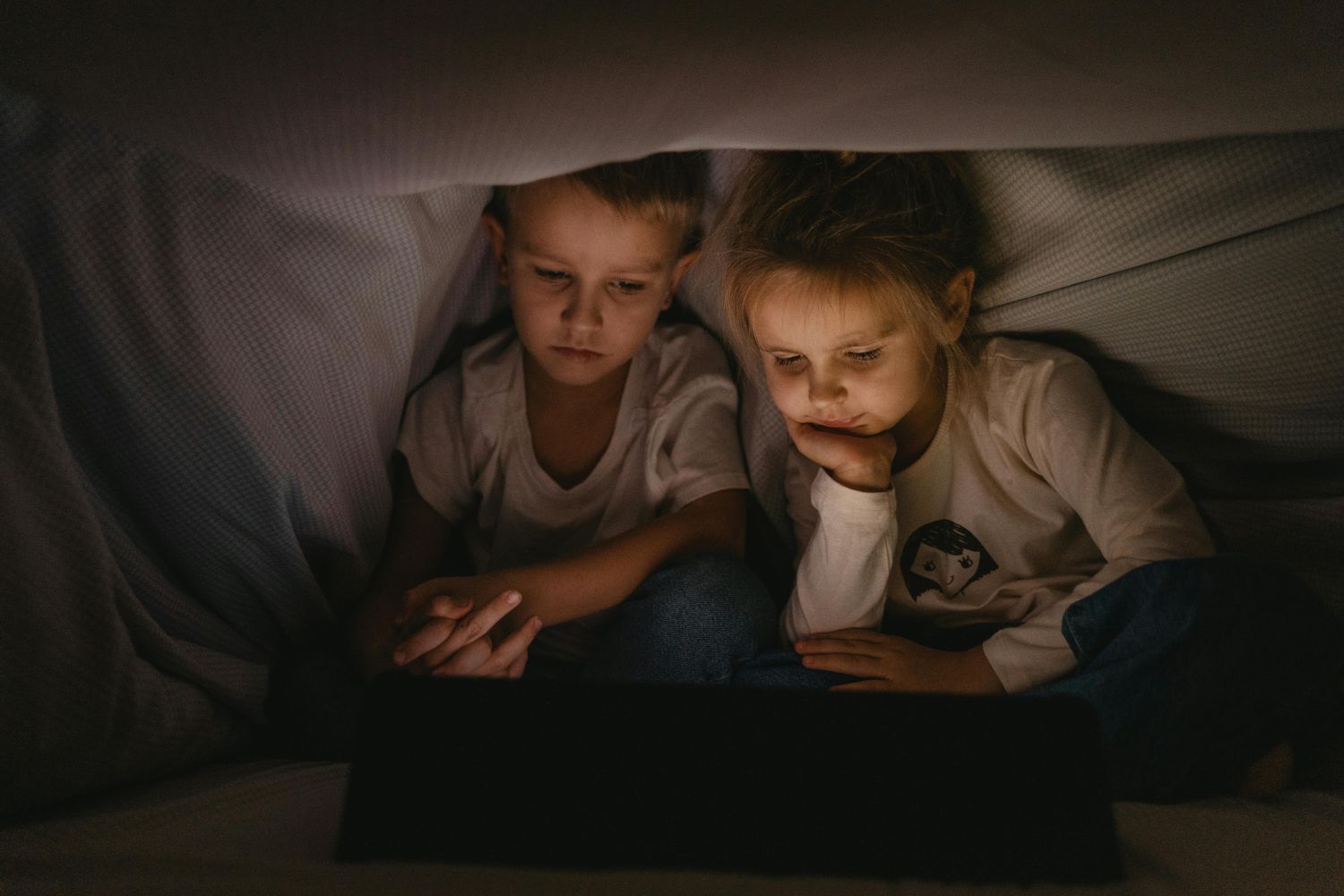

Too Much Screen Time Can Reduce Sleep Quality in Preschool-Age Children, Making Behavioural Problems Worse

Photo by Tima Miroshnichenko on Pexels

Excessive screen use by preschool-age children can lead to reduced sleep quality, exacerbating problems such as poor attention, hyperactivity and unstable mood, a new study suggests.

Peer-reviewed findings published in Early Child Development and Care show how screen time is “significantly” correlated with increased hyperactive attention problems and emotional symptoms, and with decreased sleep quality.

Additionally, the research – carried out by experts in China and Canada – demonstrates how sleep quality is also extensively correlated with decreased hyperactive attention problems, emotional symptoms and peer problems.

The findings suggest that sleep quality partially mediates the associations between screen time and hyperactive attention problems, and between screen time and emotional symptoms.

“Our results indicate that excessive screen time can leave the brains of preschool children in an excited state, leading to poor sleep quality and duration,” says corresponding author Professor Yan Li, an expert in preschool education from Shanghai Normal University.

“This poor sleep may be due to postponed bedtimes caused by screen viewing and the disruption of sleep patterns due to overstimulation and blue-light exposure. Screen use might also displace time that could have been spent sleeping and increase levels of physiological and psychological arousal, leading to difficulties in falling asleep,” adds lead author Shujin Zhou, a doctor of psychology, from Shanghai Normal University.

In generating the results, Dr Zhou and colleagues surveyed the mothers of 571 preschool children, aged between three and six years old, in seven public kindergartens in Shanghai, China.

The mothers reported the amount of time their child spent watching electronic screens (TV, smartphones, computers or other devices) each day during the previous week. They then answered questions to assess any behavioural problems their child might have, including: hyperactive attention difficulties, emotional symptoms such as frequent complaints of feeling unwell, and peer problems such as being lonely or preferring to play alone. Finally, the mothers responded to questions assessing their child’s sleep quality and duration.

“Our results suggest the presence of a positive feedback loop, wherein increased screen time and sleep disturbances exacerbate each other through cyclic reinforcement, heightening the risk of hyperactive attention problems, anxiety and depression,” adds co-author Dr Bowen Xiao, an expert in children’s socio-emotional functioning and developmental psychopathology, at the Department of Psychology, Carleton University in Canada.

The author team, which also includes professionals from Shenzhen Xili Kindergarten, suggest their findings could help toward future treatments and interventions.

“Understanding the role of screen use in the lived experiences of preschool-age children and its link to behavioural problems during the Covid-19 pandemic is crucial,” says Dr Zhou.

“The implications of our study are two-fold: first, controlling screen use in preschool-age children can help alleviate behavioural problems and poor sleep quality, and second, sleep interventions and treatments can be effective in mitigating the adverse effects of screen time on behavioural issues.”

However, the study does have several limitations – these include the fact that all data from the mothers “cannot exclude the biases from subjective perspective”.

The researchers suggest, to mitigate this, future studies should monitor sleep quality via scientific instruments.